Somali Poetry & Culture

For newly founded nations in Africa emerging in the aftermath of European colonialism, cities often evoked suspicion from their new leaders. Although the history of Mogadishu extends well beyond its Italian colonial history, the modes of development and extractive capitalism that helped figure mid-nineteenth-century Mogadishu created ennui for the new regime. Concurrently, however, the impulses to fashion a nation state built on the artificial borders of European colonialism necessitated cities like Mogadishu—cities where the surplus of labor and time could help to catalyze cultural production and concretize the post-WWII conception of nationhood, a conception fundamental to the potential success of the governing regime.

The

nation of Somalia comprises two colonial territories—British and Italian

Somaliland. However, the Somali people and language extend into parts of Kenya,

Ethiopia, and Djibouti, an extension that’s created significant tensions

throughout the twentieth century, instigating multiple Cold War-era military

interventions and a genocide that killed 200,000 Somalis.

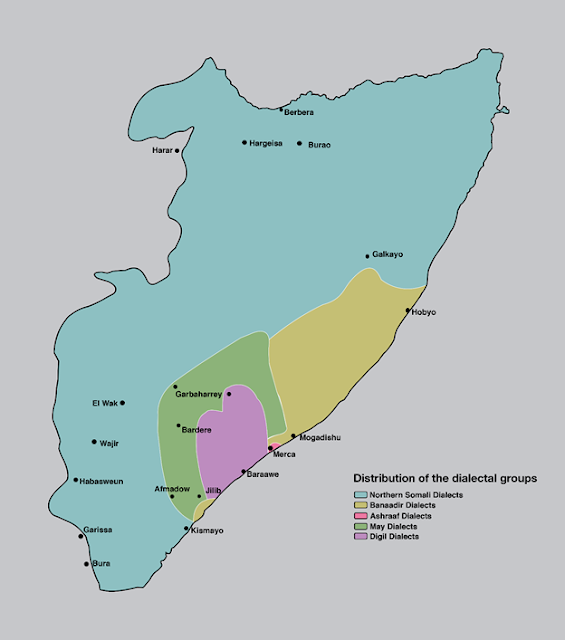

Somali

culture itself coalesces around a common language—Somali. One of the most

documented Cushitic language, Somali language itself comprises multiple

dialects that are spoken in different regions of the country. The Somali

language has a strong oral history, which has helped to cement Somali identity,

while its written history has been constantly rewritten throughout the

nineteenth and twentieth century, using Arabic, Latin, and proprietary scripts.

The

strong oral history is perhaps what both ties Somali identity together and

while also presenting challenges to Somali national unity. Examples of this oral

history in practice also present opportunities to reflect upon how linguistics

both fashion identity and (so far) prevented Somali cultural identity from

fitting seamlessly into the structures of nation-state formation.

Somali

poet Said Sheikh Samatar examines the “unwritten copyright law” observed by the

Somali poetic tradition. While chewing qat, a mildly intoxicating leaf and a

staple of Somali culture, a young poet may be questioned by his elders. In one

example from John William Johnson’s The Politics of Poetry in the Horn of Africa,

a young poet was called a charlatan by an elder. When probed about why, the elder

responded, “Because thou claimest what thou hast not laboured for.” The elders then

fetched some other elders, who could then recite the poem verbatim, attributing

it to Ugaas Nuur, a mid-nineteenth century ruler in northwestern Somalia, not

the poet that was claimed. The young poet left in silence and shame. (in Peace

and Milk, Drought and War, 228–29).

Because

of Somali poetry’s rhythmic and rhyming structure, attributions are relatively easy

to maintain within oral tradition. The attributions and subsequent ethnic or

clan-based allegiances that are preserved within this structure make it so that

Somali poetry preserves a united culture while also maintaining divisions, a

challenge that continues to haunt Somali culture and the Somali nation state.

Ciismaniya Script

Comments

Post a Comment